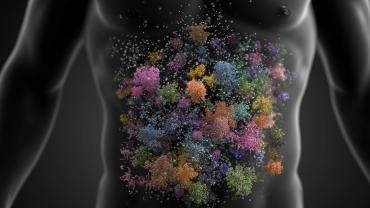

Western lifestyles, which feature low-fiber diets, overuse of antibiotics, chronic stress, and sedentary behavior, have quietly diminished the diversity of the gut microbiota. These factors often deplete fragile, beneficial (or commensal) strains that have evolved with humans for generations. In fact, bacterial diversity is significantly lower in modern, industrialized societies than in traditional settings. When these commensal bacteria are missing, the entire gut community becomes more fragile and less resilient.

Microbial resilience and stability depend on foundational organisms that help structure the environment and support cooperation among microbes. As these foundational organisms decline, the gut may lose its capacity to recover from everyday stressors. The result is often a more reactive system, not because the gut is “broken,” but because the ecological scaffolding that once supported balance has eroded. In these cases, adding individual bacterial strains without restoring the surrounding supportive network may only provide temporary support. This may be partially why probiotics work well for some and not others. It is not that the strains themselves are ineffective; it’s that the environment they’re entering may not require the specific strains being replenished. Research has shown that probiotics work best when they fill ecological niches that the host lacks.

For example, the metabolic benefit of Akkermansia muciniphila (Akkermansia) may depend on its baseline microbial abundance. In a randomized double-blind trial, compared to the placebo group, the group given 3 x 1010 CFU of live Akkermansia daily for 12 weeks, and who, at baseline, exhibited lower abundances of Akkermansia, reported significant increases in fecal Akkermansia. Or, in a paper by Suryavanshi and colleagues, the authors discuss, “…Oxalobacter formigenes-negative participants were more likely to report benefit, suggesting that the metabolic niche must be vacant for the probiotic to exert an effect.” These ideas are novel because they challenge the outdated way of thinking many companies still abide by: “the more diversity in a probiotic, the better,” because diversity is a non-negotiable factor for a healthy gut.

Why Baseline Microbiome Matters

Not all gut ecosystems begin in the same place. Large-scale microbiome research now shows that certain bacterial species are consistently associated with health, stability, and long-term persistence, regardless of geography, diet, or lifestyle. These organisms function as core or anchor taxa, persisting over time and highly interactive with other beneficial microbes. When these foundational species are present, the gut ecosystem tends to be more stable and adaptable. When they are depleted, the system becomes more vulnerable to disruption. In these gut environments, adding large numbers of random bacteria may offer temporary support, but long-term gut resiliency will not persist.

A Shift in How Gut Support is Approached

Emerging research is shifting how scientists and clinicians think about probiotic support. Rather than focusing on adding “more” bacteria or “more types” of bacteria, the emphasis is moving toward restoring the organisms that help organize and sustain the microbial ecosystem itself. In the GI tract, stability is driven by foundational, core, keystone species. These organisms help structure the environment so others may survive. Without them, even a diverse population may struggle to sustain itself. Research increasingly suggests that certain bacteria play outsized roles in maintaining microbial balance through their interactions with the gut lining and other microbes. These organisms are often referred to as keystone or foundational species.

These foundational, keystone commensal species may:

Importantly, many of these organisms are oxygen-sensitive and have historically been difficult to culture, which explains why they’ve been largely absent from conventional probiotics, including Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (F. prausnitzii) and Roseburia intestinalis (R. intestinalis).

Why “More” Isn’t Always Better

It’s easy to assume that higher colony-forming unit (CFU) counts or longer ingredient lists lead to better results. But healthy ecosystems are not built on volume alone. They are built on cooperative relationships. Without foundational species to support cross-feeding and cooperation, even diverse microbial inputs may struggle to persist. In this light, probiotic support becomes less about flooding the system and more about re-establishing structure.

In conclusion, probiotics don’t help some people and fail others by chance. Their effectiveness depends on context. When the gut ecosystem still has its foundational framework, probiotics may integrate easily. When that framework has eroded, a different approach may be needed, one that prioritizes restoring resilience rather than layering on temporary solutions. If probiotics haven’t delivered the support typically expected, it may not be a matter of trying more products. It may be a matter of rebuilding what’s missing.

Learn more about the human microbiome:

The Gut Ecosystem: Why Diversity Matters

What Are Keystone Probiotics Species?

Two Next-Generation Probiotics You Should Know About: Anaerostipes and Akkermansia

By Bri Mesenbring, MS, CNS, LDN